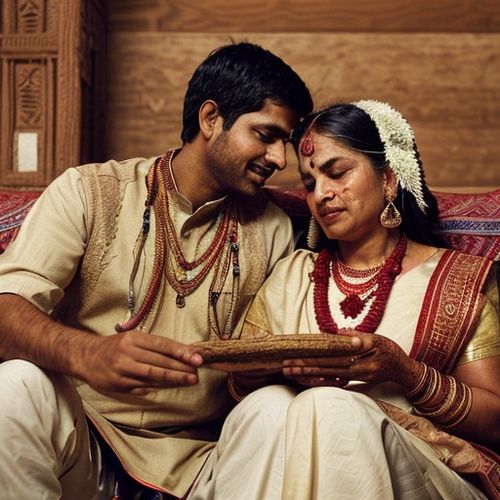

The concept of "sotsukon" or in Japan has been gaining traction in recent years, challenging traditional notions of marriage and aging. Unlike divorce, which carries a stigma in many societies, sotsukon represents a mutual decision by long-married couples to part ways amicably after their children have grown up. This phenomenon reflects broader societal shifts in Japan, where individualism is slowly taking root amidst a deeply collectivist culture. The trend is particularly notable among baby boomers who, after decades of fulfilling familial obligations, are now prioritizing personal happiness and freedom.

At its core, sotsukon is about redefining relationships in later life. Many couples who choose this path describe their marriages as having run their natural course. They often speak of a gradual emotional distance that grows over years, not out of animosity but simply from evolving priorities. The Japanese emphasis on harmony makes this arrangement appealing—it allows couples to avoid the bitterness of divorce while embracing new beginnings. Interestingly, financial independence plays a crucial role; women who stayed home to raise children are now entering the workforce in their 50s and 60s, gaining the economic means to support separate lives.

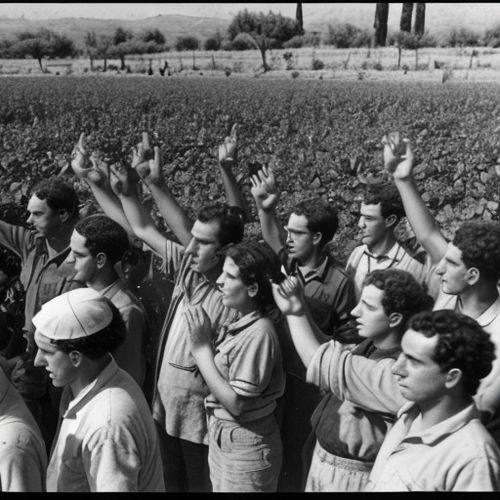

Social commentators have noted that sotsukon mirrors Japan's rapidly aging population and declining birthrate. With life expectancy among the highest globally, elderly Japanese are healthier and more active than previous generations, unwilling to spend their golden years in unhappy marriages. The phenomenon also intersects with changing gender roles. Post-war Japan saw rigid divisions between breadwinning husbands and homemaking wives, but younger generations view marriage as a partnership of equals. When these expectations clash with reality in long-term marriages, sotsukon becomes an attractive alternative to either maintaining the status quo or pursuing messy divorces.

Media portrayal of sotsukon tends to focus on celebrity cases, like actors and musicians who publicly announce their "graduation from marriage." However, the reality for ordinary couples involves complex emotional negotiations. Some maintain friendly relationships after separating, even celebrating holidays together with their grown children. Others completely reinvent themselves—taking up new hobbies, traveling solo, or even dating again. Critics argue this trend might weaken family structures, but proponents counter that it prevents the resentment that often poisons multigenerational households in Japan's cramped living conditions.

The legal framework surrounding sotsukon remains ambiguous since Japanese law doesn't officially recognize this arrangement. Couples must still legally divorce if they wish to separate assets or remarry, leading some to maintain marital status on paper while living independently. This gray area creates challenges regarding inheritance rights, pension benefits, and healthcare decisions. Some forward-thinking lawyers have begun offering "sotsukon contracts"—private agreements outlining financial arrangements and caregiving responsibilities as couples age separately.

Economically, sotsukon is creating ripple effects across industries. Real estate agencies report growing demand for small apartments tailored to single seniors. Travel companies market "silver solo" vacation packages. Even furniture manufacturers are designing compact household goods for downsized lifestyles. This commercial response underscores how sotsukon isn't just a personal choice but a demographic shift influencing market trends. Meanwhile, sociologists observe that children of sotsukon couples often express initial shock but later appreciate their parents' honesty about seeking happiness.

Looking ahead, sotsukon may represent the vanguard of global marital trends as populations age worldwide. Scandinavian countries already see similar patterns of late-life separations, though without the distinct cultural framing found in Japan. As more societies confront the reality of longer lifespans and evolving relationship expectations, the Japanese model of conscious uncoupling in later years might offer valuable insights. What makes sotsukon uniquely Japanese is its emphasis on mutual respect and timing—viewing marital separation not as failure but as the next appropriate phase in life's journey.

By Sophia Lewis/Apr 19, 2025

By Joshua Howard/Apr 19, 2025

By Laura Wilson/Apr 19, 2025

By James Moore/Apr 19, 2025

By Eric Ward/Apr 19, 2025

By Ryan Martin/Apr 19, 2025

By Elizabeth Taylor/Apr 19, 2025

By Samuel Cooper/Apr 19, 2025

By Benjamin Evans/Apr 19, 2025

By Christopher Harris/Apr 19, 2025

By Olivia Reed/Apr 19, 2025

By Megan Clark/Apr 19, 2025

By Michael Brown/Apr 19, 2025

By William Miller/Apr 19, 2025

By Sarah Davis/Apr 19, 2025

By Joshua Howard/Apr 19, 2025

By Ryan Martin/Apr 19, 2025

By Eric Ward/Apr 19, 2025

By Jessica Lee/Apr 19, 2025

By David Anderson/Apr 19, 2025