The Japanese divorce mediation system represents a unique cultural and legal approach to marital dissolution that prioritizes harmony over adversarial proceedings. Unlike Western nations where litigation often dominates divorce processes, Japan's family court mediation (chōtei) reflects deeply ingrained societal values of consensus-building and face-saving. This system, while not without critics, offers fascinating insights into how legal frameworks adapt to cultural priorities.

Historical Context and Cultural Foundations

Japan's preference for mediation over litigation dates back centuries, rooted in Confucian ideals that view interpersonal harmony as paramount. The modern family court system established in 1948 inherited this tradition, creating a process where approximately 90% of divorces requiring third-party intervention pass through mediation before becoming eligible for litigation. This reflects the enduring cultural belief that disputes, even deeply personal ones like marital breakdowns, should ideally be resolved through compromise rather than confrontation.

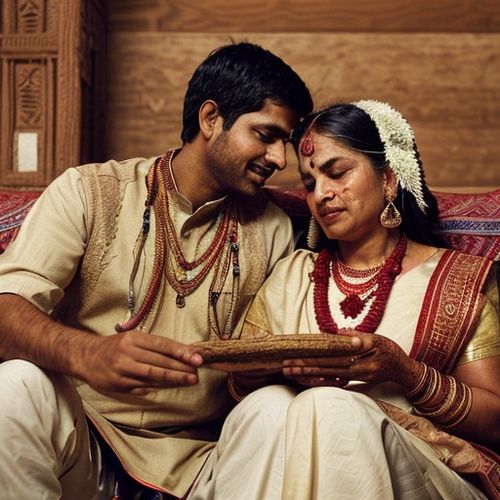

The mediation process typically involves one professional mediator and two volunteer mediators (usually citizens with life experience rather than legal training) who facilitate discussions between spouses. These sessions occur in private conference rooms rather than courtrooms, with participants seated at round tables to emphasize equality. The atmosphere deliberately avoids the formality of judicial proceedings, with mediators often serving tea to create a more relaxed environment conducive to open communication.

The Mediation Process in Practice

Initiation of divorce mediation usually begins when one spouse files a petition with the family court - interestingly, this can be done unilaterally without the other party's consent. The court then schedules sessions typically spaced several weeks apart, allowing cooling-off periods between discussions. Most cases conclude within three to six months, though complex situations involving child custody or significant assets may extend longer.

During sessions, mediators employ various techniques adapted from traditional Japanese conflict resolution methods. They might separate the spouses for private caucuses (called "benjo sesshoku") to understand each party's true concerns, as direct confrontation is culturally discouraged. The mediators then reframe positions as shared problems to solve rather than competing demands. For instance, rather than having parents argue over child custody, mediators might guide them toward discussing "how to ensure the children's happiness post-divorce."

Unique Aspects of Japanese Divorce Mediation

Several distinctive features set Japan's system apart from Western models. First, the process incorporates apology rituals - spouses are often encouraged to acknowledge their contributions to the marital breakdown, even when fault is unequal. This reflects the cultural importance of taking responsibility to restore social balance. Second, extended family members sometimes participate in later sessions, recognizing that marital dissolution affects entire kinship networks in Japan's collectivist society.

Another notable aspect is how mediators handle emotional expression. While Western mediators might encourage venting emotions, Japanese mediators more frequently redirect intense expressions into problem-solving discussions. This approach stems from cultural norms valuing emotional restraint and the belief that excessive emotional display hinders rational decision-making.

Contemporary Challenges and Reforms

Recent years have seen growing criticism of the system's handling of domestic violence cases. Critics argue the emphasis on compromise pressures victims into unsafe settlements. In response, some courts now implement protective measures like separate waiting areas and staggered arrival times. However, activists contend these changes don't go far enough in addressing power imbalances.

Another emerging issue involves international marriages, which now constitute about 3% of Japanese marriages. Cultural differences in conflict resolution styles and expectations about divorce create unique mediation challenges. Some courts have begun employing bilingual mediators and providing translated documents, but resources remain limited outside major cities.

The system also grapples with changing gender dynamics. While Japanese law mandates equal division of marital assets, mediation outcomes often reflect traditional gender roles, with wives frequently receiving primary custody of children but less favorable financial settlements. Recent high-profile cases have sparked debate about whether mediators unconsciously perpetuate gender biases despite legal equality.

Comparative Perspectives and Future Directions

When contrasted with other developed nations, Japan's mediation-centric approach yields interesting outcomes. The country's divorce rate remains relatively low (about 1.7 per 1,000 people compared to America's 2.9), though scholars debate how much credit mediation deserves versus other cultural factors. Notably, mediated divorces in Japan show lower rates of post-divorce litigation regarding enforcement of agreements - a potential advantage of the consensus-based process.

Looking ahead, Japan faces pressure to modernize its mediation system while preserving its cultural strengths. Proposed reforms include better mediator training on domestic violence, increased transparency in decision-making criteria, and expanded support services for families undergoing mediation. Some progressive judges advocate incorporating more Western-style elements like clearer guidelines for asset division, while traditionalists warn against losing the system's distinctively Japanese character.

As Japanese society continues evolving - with rising female workforce participation, growing acceptance of diverse family structures, and increasing international influence - its divorce mediation system serves as a living laboratory for how legal traditions adapt to social change. The coming decade will likely see significant modifications to the process, but its core philosophy of seeking harmonious resolutions will probably endure as a reflection of deeper cultural values.

By Sophia Lewis/Apr 19, 2025

By Joshua Howard/Apr 19, 2025

By Laura Wilson/Apr 19, 2025

By James Moore/Apr 19, 2025

By Eric Ward/Apr 19, 2025

By Ryan Martin/Apr 19, 2025

By Elizabeth Taylor/Apr 19, 2025

By Samuel Cooper/Apr 19, 2025

By Benjamin Evans/Apr 19, 2025

By Christopher Harris/Apr 19, 2025

By Olivia Reed/Apr 19, 2025

By Megan Clark/Apr 19, 2025

By Michael Brown/Apr 19, 2025

By William Miller/Apr 19, 2025

By Sarah Davis/Apr 19, 2025

By Joshua Howard/Apr 19, 2025

By Ryan Martin/Apr 19, 2025

By Eric Ward/Apr 19, 2025

By Jessica Lee/Apr 19, 2025

By David Anderson/Apr 19, 2025