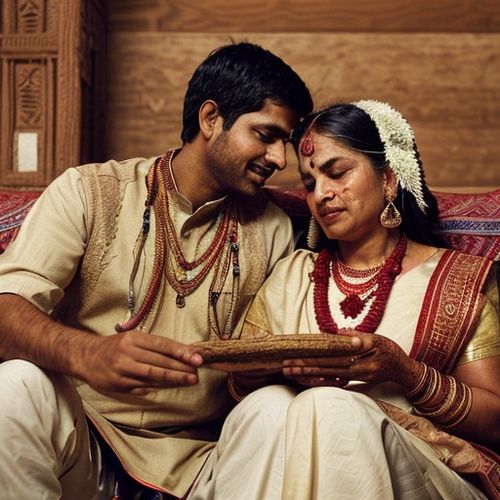

The institution of marriage in Brazil has undergone significant transformations in recent decades, with one of the most notable trends being the steady decline of religious ceremonies. This shift reflects broader changes in Brazilian society, where traditional religious practices are increasingly giving way to secular alternatives or simply being abandoned altogether.

For generations, the Catholic wedding ceremony represented the gold standard for Brazilian couples. The grand church weddings with elaborate white dresses, extensive guest lists, and full Mass celebrations were seen as the proper way to begin married life. However, recent statistics from the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) reveal that religious marriages now account for less than 40% of all unions formalized in the country - a dramatic drop from nearly 80% in the 1970s.

The reasons behind this decline are complex and multifaceted. Experts point to several interconnected factors including the rising costs of religious ceremonies, changing attitudes among younger generations, the growing secularization of Brazilian society, and the increasing acceptance of alternative family structures. What was once considered scandalous - living together without marriage or having children outside wedlock - has become commonplace across all social classes.

Economic considerations play a significant role in this trend. The full traditional Catholic wedding with all its trappings can cost upwards of R$50,000 in major cities like São Paulo or Rio de Janeiro. Many young couples simply cannot justify such expenses when civil ceremonies offer legal recognition at a fraction of the cost. "Why spend on a church wedding when that money could go toward a home down payment or our children's education?" asks Mariana Silva, a 28-year-old marketing professional from Belo Horizonte who opted for a civil ceremony last year.

The Catholic Church's dwindling influence in Brazilian society has also contributed to the marriage decline. While Brazil remains the world's largest Catholic country by nominal numbers, regular church attendance has fallen sharply, particularly among urban youth. Many Brazilians now identify as spiritual but not religious, or have switched to evangelical denominations that often have less rigid requirements for marriage ceremonies.

Demographic changes tell an important part of the story. Brazil's urban population has grown exponentially, and city dwellers tend to marry later (if at all) and have different priorities than their rural counterparts. The average age for first marriage in Brazil has risen from 22 for women and 25 for men in 1990 to 28 and 30 respectively today. By the time many urban professionals consider marriage, religious considerations often take a backseat to practical concerns.

Legal changes have also facilitated the shift away from religious unions. Until the 1970s, civil marriages in Brazil required a religious ceremony first. The elimination of this requirement, along with the growing acceptance of common-law marriages (união estável) with full legal rights, has removed much of the practical incentive for church weddings. Many couples now view the civil ceremony as sufficient, with some opting for non-religious celebratory events afterward.

The Catholic Church has not remained passive in the face of these changes. Some dioceses have introduced cheaper "social wedding" packages and streamlined requirements to make religious marriages more accessible. "We understand that young couples face different challenges today," says Father Antônio Carlos of the Archdiocese of Rio de Janeiro. "The Church must adapt while maintaining the sacred nature of the sacrament."

Interestingly, the decline hasn't been uniform across all religious groups. While Catholic weddings have decreased sharply, evangelical Protestant ceremonies have seen modest growth, reflecting that denomination's expanding influence in Brazilian society. However, even among evangelicals, civil marriages are becoming more common, suggesting the trend toward secularization cuts across religious lines.

Social class dynamics add another layer to this complex picture. Among Brazil's economic elite, extravagant religious weddings remain popular status symbols, often featured in society magazines and social media. For the working class and poor, however, the costs are often prohibitive, leading many to forego formal marriage altogether. The middle class appears to be driving much of the shift toward civil ceremonies, viewing them as more practical and modern.

The pandemic accelerated these trends dramatically. With churches closed or operating under restrictions in 2020-2021, many couples who might have opted for religious ceremonies had civil marriages instead. Post-pandemic, a significant portion never rescheduled their church weddings, having discovered that the civil union satisfied all their practical needs without the additional expense and complication of a religious ceremony.

Some sociologists argue that the decline of religious marriage reflects deeper changes in how Brazilians view commitment and family. "Young people today prioritize emotional fulfillment and practical compatibility over religious or social expectations," notes Dr. Ana Paula Mendes of the University of São Paulo. "For many, a religious ceremony feels like performing for others rather than celebrating their authentic relationship."

This doesn't mean religion has disappeared from Brazilian marriages entirely. Many couples who choose civil ceremonies still incorporate religious elements like prayers or scripture readings, creating hybrid celebrations that reflect their personal beliefs without adhering to institutional requirements. Others maintain spiritual aspects while rejecting organized religion's role in their union.

The legal landscape continues to evolve as well. Recent court rulings have made it easier for non-religious organizations to perform weddings, and humanist ceremonies are gaining popularity among secular Brazilians. Some couples are even designing completely personalized ceremonies that reflect their unique values and relationship stories.

Looking ahead, most experts believe the decline of religious marriages in Brazil will continue, though likely at a slower pace. The Catholic Church and evangelical groups will probably retain some share of the marriage market, particularly among more devout populations. However, the era when religious ceremonies dominated Brazilian matrimony appears to have ended, giving way to a more diverse, personalized approach to celebrating unions.

This transformation mirrors similar trends in other historically Catholic countries, but with distinct Brazilian characteristics. The country's unique blend of religious syncretism, social inequality, and rapid urbanization has created a marriage landscape where tradition and modernity exist in tension. What emerges in the coming decades may redefine not just how Brazilians marry, but how they understand the very nature of commitment and family in the 21st century.

By Sophia Lewis/Apr 19, 2025

By Joshua Howard/Apr 19, 2025

By Laura Wilson/Apr 19, 2025

By James Moore/Apr 19, 2025

By Eric Ward/Apr 19, 2025

By Ryan Martin/Apr 19, 2025

By Elizabeth Taylor/Apr 19, 2025

By Samuel Cooper/Apr 19, 2025

By Benjamin Evans/Apr 19, 2025

By Christopher Harris/Apr 19, 2025

By Olivia Reed/Apr 19, 2025

By Megan Clark/Apr 19, 2025

By Michael Brown/Apr 19, 2025

By William Miller/Apr 19, 2025

By Sarah Davis/Apr 19, 2025

By Joshua Howard/Apr 19, 2025

By Ryan Martin/Apr 19, 2025

By Eric Ward/Apr 19, 2025

By Jessica Lee/Apr 19, 2025

By David Anderson/Apr 19, 2025